Discover why the Gudimallam Lingam stands unique among thousands of Shiva temples—featuring a rare anthropomorphic carving, hunter deity attributes, and the oldest known Shiva representation dating to 3rd century BCE. Explore this archaeological marvel’s secrets with temple historian Dr. Iyengar.

In the realm of ancient religious artifacts, few objects stand as mysteriously captivating as the Gudimallam Lingam. Nestled in the unassuming village of Gudimallam in Andhra Pradesh’s Chittoor district, this remarkable Shiva Lingam has puzzled and fascinated archaeologists, historians, and devotees for generations. While India houses thousands of Shiva Lingams, each with its own significance and design, the Gudimallam Lingam possesses distinctive characteristics that set it apart from every other known Lingam in the country—and perhaps the world.

As a researcher who has spent over a decade studying ancient Hindu iconography, I’ve visited numerous Shiva temples across India. However, my first encounter with the Gudimallam Lingam left me utterly mesmerized. The unique combination of explicit anatomical representation and detailed anthropomorphic carving creates an iconographic marvel unparalleled in Hindu sacred art. This article explores what makes this ancient artifact so exceptional and why it holds such profound significance in understanding the evolution of Shaivite worship.

The Anthropomorphic Marvel: A Standing Shiva Figure on a Phallic Form

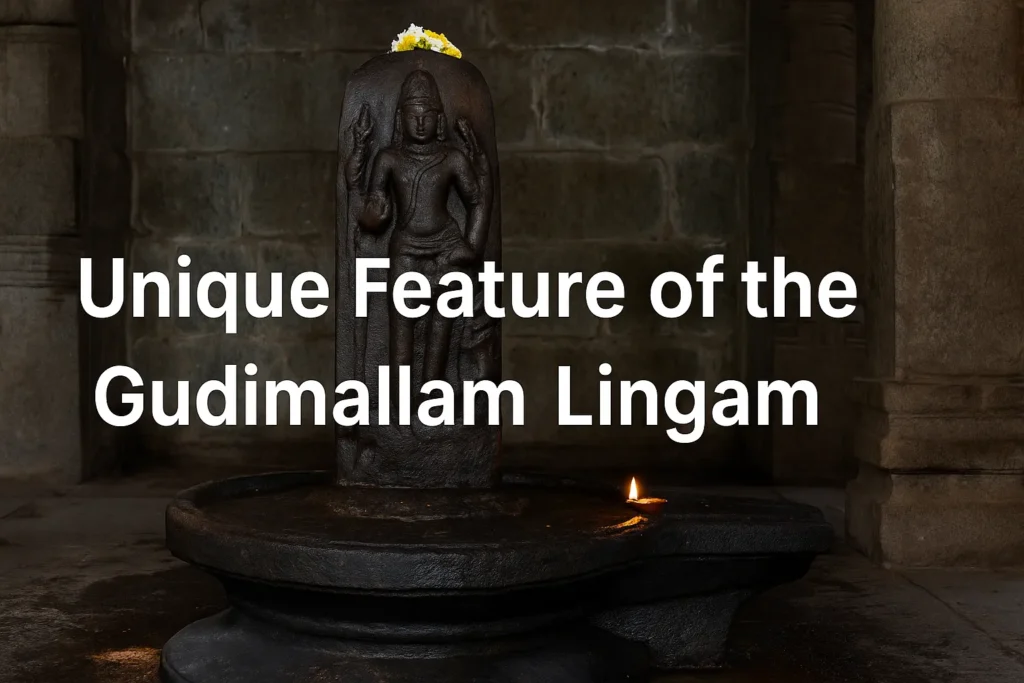

The most striking and unique feature of the Gudimallam Lingam is its integration of a full-length, high-relief figure of Lord Shiva carved directly onto the front of an otherwise anatomically accurate phallic form. This extraordinary combination of representational anthropomorphic sculpture with the symbolic phallus makes it completely unprecedented in Indian art.

While later Lingams evolved toward abstract symbolism, the Gudimallam Lingam represents a transitional phase in Hindu iconography where literal and symbolic elements coexist in a single artifact. According to renowned art historian J.C. Harle, this is “the only sculpture of any importance” to survive from ancient South India before the elaborate traditions of the Pallava dynasty emerged in the 7th century CE.

The Shiva figure is carved with remarkable skill and attention to detail. Standing in a frontal position (sthanaka), the deity is depicted with:

- A two-armed form (dwibhuja), unusual compared to the more common four-armed (chaturbhuja) representations in later Shiva iconography

- An elaborate coiffure with braided and curled hair arranged in the jatabhara fashion, predating the more standardized jatamukuta (crown of matted hair) seen in later depictions

- Multiple ornate earrings and jewelry adorning the neck and arms

- A distinctive girdle or waistband with a dangling central tassel

- A thin, transparent fabric draped around the waist (dhoti), visible yet revealing the anatomical form beneath

This level of artistic sophistication in such an early period demonstrates an advanced sculptural tradition that had already developed significant iconographic conventions.

The Hunter’s Attributes: Unique Symbolism of Weapons and Animal

Another distinctive aspect of the Gudimallam Lingam is its depiction of Shiva as a hunter or fierce deity—a representation rarely seen in such early artifacts. In his right hand, Shiva holds a ram or antelope by its hind legs, with the animal’s head hanging downward. His left hand carries a small water pot or vessel, while a battle axe (parashu) rests upon his left shoulder.

This combination of attributes is highly unusual in Shiva iconography. While later depictions sometimes show Shiva with a deer or antelope, it’s typically held gently rather than as prey. The battle axe on the shoulder further distinguishes this representation, as it became more commonly associated with Parashurama (an avatar of Vishnu) in later Hindu art.

Art historians suggest this unusual combination may represent a very early form of Shiva as Pashupati (Lord of Animals) or as a tribal hunter deity who was gradually incorporated into mainstream Brahmanical worship. The water pot might symbolize Shiva’s association with rivers and the life-giving properties of water, particularly relevant in an agricultural society.

What makes these attributes particularly noteworthy is their appearance in such an early timeframe. As archaeologist T.A. Gopinatha Rao first noted when he documented the Lingam in 1911, these elements provide crucial evidence for understanding how Shiva’s iconography evolved over time.

The Enigmatic Dwarf: Standing Upon Apasmara or Yaksha

Perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of the Gudimallam Lingam is the crouching dwarf-like figure upon whose shoulders Lord Shiva stands. This feature has generated considerable scholarly debate about both its identity and symbolic meaning.

Three primary interpretations have emerged:

- Apasmara Purusha: Many scholars identify the figure as Apasmara, the demon of ignorance or forgetfulness whom Shiva tramples in his Nataraja (cosmic dancer) form. This would make the Gudimallam Lingam an exceptionally early example of this iconographic element.

- Gana or Attendant: Others suggest it may represent a mischievous gana (attendant) of Shiva, symbolizing the deity’s authority over supernatural beings.

- Yaksha: Some scholars, including those who have studied the physiognomic features of the figure, argue it closely resembles the yaksha figures (nature spirits) depicted at early Buddhist sites like Bharhut and Sanchi. The figure has “pointed animal ears” and what some describe as “fish-shaped feet and conch-shaped ears,” suggesting a water spirit.

What makes this feature particularly unique is that the dwarf appears cheerful rather than subjugated. In contrast to later depictions where Apasmara appears crushed or tormented beneath Shiva’s foot, the Gudimallam figure seems almost to be willingly supporting the deity—perhaps representing a harmonious relationship between Shiva and nature spirits, or between dominant Brahmanical traditions and indigenous faiths.

No other early Shiva Lingam incorporates this element in quite the same way, making it a distinctive iconographic feature that offers valuable insights into the religious syncretism of ancient South India.

The Seven-Sided Shaft: Geometric Precision in Design

While most Shiva Lingams have a cylindrical or rounded shaft, the Gudimallam Lingam features a seven-sided shaft with faces of unequal length. This heptagonal design demonstrates a sophisticated geometric conception rarely seen in other Lingams.

According to archaeological documentation, the shaft has:

- Two longer faces (about 6 inches each) forming the front where the Shiva figure is carved

- Two side faces (about 4 inches each) at right angles to the figure

- Three faces at the rear, with one central longer face and two shorter ones joining the back to the sides

This intentional geometric design suggests that the artifact was created with precise mathematical principles in mind, rather than simply being a naturalistic representation. The number seven holds special significance in Hindu cosmology, potentially representing the seven chakras, the seven worlds, or the seven mother goddesses (Saptamatrikas).

No other known early Lingam displays this specific heptagonal configuration. While some later Lingams have multiple faces (typically eight, representing the eight directions), the asymmetrical seven-sided design of the Gudimallam Lingam remains unique.

The Ancient Origins: Dating to the Pre-Common Era

What truly sets the Gudimallam Lingam apart is its remarkable antiquity. Archaeological evidence, stylistic analysis, and comparative studies have dated this artifact to between the 3rd century BCE and the 1st century CE, with most scholars placing it around the 2nd-1st century BCE.

Several factors support this early dating:

- Stylistic Comparison: The distinctive physiognomy of both the Shiva figure and the crouching dwarf bear striking similarities to sculptures from the early Buddhist sites of Bharhut and Sanchi, which date to approximately the 2nd century BCE.

- Numismatic Evidence: Copper coins discovered at Ujjain, dating to the 3rd century BCE, contain figures resembling the Gudimallam Lingam, suggesting its iconography was already established by this period.

- Archaeological Context: Excavations conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India in 1973 unearthed Black and Red Ware pottery sherds from the 2nd or 3rd century CE in the vicinity of the Lingam, helping to establish the chronology of the site.

While there are other ancient Lingams in India, such as the Bhita Lingam (now in Lucknow Museum), none combine such early origins with the elaborate anthropomorphic carving and unique iconographic features of the Gudimallam example. The Bhita Lingam, dating to about the 2nd century BCE, has directional faces carved on the pillar, but lacks the full-figure relief sculpture that makes Gudimallam so exceptional.

The Explicit Anatomical Representation: Unmodified Phallic Form

Unlike the vast majority of Shiva Lingams found across India today, which have evolved into abstract symbolic forms, the Gudimallam Lingam retains an unmistakably anatomical phallic shape. Scholar T.A. Gopinatha Rao described it as “shaped exactly like the original model, in a state of erection,” with the glans penis clearly differentiated from the shaft by a wider portion with a deep slanting groove about a foot from the top.

This realistic representation provides crucial evidence about the early origins of Lingam worship. While later theological traditions often downplayed or reinterpreted the phallic symbolism, the Gudimallam Lingam confirms that early Shaivite worship incorporated explicit generative symbolism.

However, it’s important to note that religious scholars like Stella Kramrisch have cautioned against interpreting this explicit form as merely a fertility symbol. In the context of Shaivite philosophy, the ithyphallic representation connotes “Urdhva Retas” (the ascent of vital energy) and represents spiritual potency, asceticism, and the sublimation of physical passions rather than their expression.

The Gudimallam Lingam thus occupies a unique position in demonstrating the transition from literal to symbolic representation in Hindu sacred art, preserving an iconographic stage largely lost in later traditions.

The Architectural Context: An Apsidal Sanctum

Another distinctive feature of the Gudimallam Lingam is its unusual architectural setting. The sanctum (garbhagriha) housing the Lingam is apsidal or semi-circular, curving behind the Lingam. This architectural style is extremely rare in Hindu temples but has parallels in early Buddhist structures.

Archaeological investigations revealed that the site had a brick apsidal temple surrounding the Lingam by the 2nd or 3rd century CE, suggesting the Lingam itself predates even this early structure. This reinforces the theory that the Lingam was originally installed in the open air, surrounded by a simple stone enclosure, before being incorporated into increasingly elaborate temple structures over the centuries.

The current temple building largely dates to the Chola and Vijayanagara periods (11th-16th centuries CE), representing multiple phases of construction and renovation around the ancient central Lingam. This architectural evolution reflects the continuing reverence for the artifact across changing dynasties and religious expressions.

The combination of an apsidal shrine with a Lingam that bears anthropomorphic carving represents a unique fusion of architectural and sculptural traditions not found elsewhere in India.

The Unbroken Worship: Continuous Reverence Through Millennia

Perhaps one of the most remarkable aspects of the Gudimallam Lingam is its continuous history of worship spanning over two millennia. Despite numerous political, cultural, and religious changes in the region, the Lingam has remained an active focus of devotion from antiquity to the present day.

This continuity is exceptionally rare for such an ancient religious artifact. While many ancient temples and shrines were abandoned, destroyed, or repurposed throughout India’s complex history, the Gudimallam Lingam has maintained its sacred status uninterrupted across the centuries.

Since 1954, the site has been protected by the Archaeological Survey of India as a monument of national importance, while still allowing traditional worship to continue—a delicate balance between preservation and living religious practice. This dual status as both archaeological treasure and active religious site adds another layer to its uniqueness.

The temple, now known as the Parasurameswara Temple, continues to draw devotees and scholars alike, with rituals like the Rudrabhisheka performed regularly for the ancient Lingam. This represents one of the longest continuous traditions of worship centered on a single religious artifact anywhere in the world.

The Scholarly Significance: Evidence of Indigenous Traditions

Beyond its religious importance, the Gudimallam Lingam holds tremendous value for understanding the development of Hindu iconography and the syncretism of various religious traditions in ancient India.

Some scholars have suggested that the distinctive features of the figure depicted on the Lingam—including its broad, squat physique, thick curly hair, high cheekbones, and thick lips—point to indigenous and local antecedents that predate Indo-Aryan (Brahmanical) influence. This raises fascinating questions about the complex interplay between local cult practices and the evolving Brahmanical tradition.

The location of the Lingam in South India, far from the traditional centers of early Brahmanical culture in the Gangetic plain, further supports the possibility of distinctive regional influences on its creation. The Gudimallam Lingam may represent a crucial transitional point where indigenous religious practices were being incorporated into the developing Brahmanical tradition.

This archaeological evidence challenges simplistic narratives about the development of Hinduism and suggests a more complex process of religious exchange and synthesis that characterized ancient Indian spiritual life.

Comparative Analysis with Other Ancient Lingams

To truly appreciate the uniqueness of the Gudimallam Lingam, it’s instructive to compare it with other ancient Lingams found across India:

The Bhita Lingam (Lucknow Museum)

Dating to approximately the 2nd century BCE, the Bhita Lingam features four directional faces (chaturmukha) on the pillar and a Brahmi script inscription at the bottom. Above the faces, it has the bust of a male figure holding a vase in his left hand and displaying the abhaya (fear-not) mudra with his right.

While contemporaneous with Gudimallam, the Bhita Lingam represents a different iconographic approach, with multiple directional faces rather than a single prominent figure. It lacks the elaborate narrative quality of the Gudimallam sculpture, focusing instead on symbolic directional guardianship.

Mathura Lingams (1st-3rd century CE)

Archaeological excavations at Mathura have revealed several early Lingams dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. Some feature a standing Shiva figure (similar to Gudimallam but typically less detailed), while others have one or four faces around the pillar.

While showing certain parallels to Gudimallam, these Lingams generally date to a later period and lack the unique combination of features—especially the figure standing on a dwarf—that distinguishes the Andhra Pradesh example.

Later South Indian Lingams

In contrast to these early examples, later South Indian Lingams typically abandoned anthropomorphic representation in favor of abstract symbolism. They were often divided into three distinct sections representing Brahma (base), Vishnu (middle), and Shiva (top), emphasizing the cosmic unity of the Hindu trinity rather than the specific identity of Shiva as a hunter or warrior.

The evolution away from explicit anatomical representation toward abstract symbolism marks a significant theological shift that the Gudimallam Lingam helps to contextualize as an early transitional form.

The Cultural Context: Understanding Early Shaivism

The unique features of the Gudimallam Lingam offer valuable insights into the development of Shaivism (worship of Shiva) in ancient India. The artifact appears to represent a transitional period when more explicit fertility and tribal hunter symbolism was being integrated into formal religious structures.

Several cultural insights emerge from studying this unique artifact:

- Integration of Tribal Deities: The hunter attributes and association with animals suggest the incorporation of tribal or local hunter deities into mainstream worship.

- Early Visualization of Abstract Concepts: The Lingam demonstrates an early attempt to give visual form to abstract theological concepts, bridging the gap between concrete ritual objects and philosophical ideas.

- Regional Variations in Worship: The distinctive style shows that even in ancient times, significant regional variations existed in religious iconography, challenging any notion of a monolithic Hindu tradition.

- Artistic Sophistication: The technical skill displayed in carving the high-relief figure attests to a well-developed artistic tradition in Southern India much earlier than previously recognized.

These cultural insights make the Gudimallam Lingam not just a religious artifact but a crucial document for understanding the rich tapestry of ancient Indian religious life and practice.

Visiting the Ancient Marvel: Practical Information

For those interested in witnessing this extraordinary artifact firsthand, the Gudimallam Lingam remains accessible to visitors at the Parasurameswara Temple in Gudimallam village. The site is located approximately 15 kilometers southeast of Tirupati city and about 10 kilometers northeast of Renigunta Junction.

The temple is typically open from early morning until noon and again in the evening, though specific visiting hours may vary. As an active religious site, visitors should observe appropriate temple etiquette, including modest dress and respectful behavior.

The nearest major transportation hub is Tirupati, which has excellent rail, road, and air connections to major cities across India. From Tirupati, local transportation options include buses, shared autos, and taxis to reach Gudimallam.

For those planning a pilgrimage or scholarly visit to this remarkable site, combining it with a tour of other historical temples in the region, such as those at Tirupati and Kalahasti, provides a comprehensive understanding of the architectural and religious traditions of the area.

A Singular Treasure of Ancient Indian Art

The Gudimallam Lingam stands as a unique testament to the artistic, religious, and cultural sophistication of ancient India. Its singular combination of features—the anthropomorphic carving, the explicit phallic form, the hunter attributes, the supporting dwarf figure, the heptagonal design, and its incredible antiquity—makes it truly one of a kind among all Shiva Lingams in India.

Beyond its religious significance, this remarkable artifact continues to challenge our understanding of early Hindu iconography and the complex interplay of indigenous and Brahmanical traditions in forming what we now recognize as Hinduism. The Gudimallam Lingam demonstrates that ancient Indian religious expression was far more diverse and nuanced than often portrayed, with regional variations and syncretistic elements creating rich tapestries of meaning.

For devotees, historians, archaeologists, and art lovers alike, the Gudimallam Lingam represents an irreplaceable treasure—a window into an ancient world of faith and artistic expression that continues to inspire wonder and reverence more than two millennia after its creation.

About the Author:

Dr. Ananth Kumar Iyengar is a professional historian and writer with a deep passion for Indian mythology. For over two decades, he has delved into the legends and lore of temples across India, with a special focus on Shaivite shrines and iconography. His writings bring to life the divine tales of ancient Hindu temples and the spiritual history of sacred places. Known for his engaging storytelling style, Dr. Iyengar’s blogs provide readers with a profound understanding of temples’ historical and mythological importance.

Email: ananth.iyengar@vidzone.in